Traditional Methods of Black Magic

Spooky action at a distance

Competition is embedded in social living, as individuals seek to control and monopolize access to scarce resources—status, partners, material goods. Across societies, there are a variety of means one may use to overcome a competitor. Derogating an adversary through rumors and gossip. Direct physical force. Greater achievement in socially recognized domains, such as being a better craftsman or hunter or warrior. Recruitment of supporters.

There is another method, however, that has been historically widespread, but less widely discussed, and less palatable to those schooled in the modern sciences. That of aggression channeled through supernatural means.

Among Tucano horticulturalists of the northwest Amazon, there was an extended process by which a shaman could lead his intended victim to their death. The shaman would procure pieces of the unfortunate target—fingernails, a lock of hair, or bits of skin—and boil it with capsicum (a pepper). Once the brew was heated the victim would begin to suffer stomach cramps. Boiling would continue on and off for three days—while heated, the victim would experience pain, which would dwindle as the concoction cooled.

On the third day, the shaman would hover over the pot and sing, commanding his unknowing target to eat parts of their own body, accompanying these instructions with extensive gestures. The victim would start to vomit continuously. As the pot boiled the shaman would perform a stilted dance around it. The victim staggers and bites their tongue. The spirit of the victim would now appear over the pot in the form of a butterfly, before falling into the potion. The shaman then breaks the pot and the victim immediately falls to their death.

Among Ovambo pastoralists of southern Africa, a similar method is utilized. A resentful adversary procures some spittle, or a piece of clothing, or even urine, from his hated foe, and brings it to a sorcerer he has solicited the services of. The sorcerer takes the detritus of his intended prey and puts it in a pot over a fire, along with some special herbs and grasses, reciting ‘So-and-so, may he soon die’. The ashes from materials are then buried in a hole and covered with sand. A stick is placed at the location to resemble a grave, and soon the person will die.

While these elaborate methods of supernatural destruction have many culturally specific details, they reflect common practices of magical killing across diverse societies.

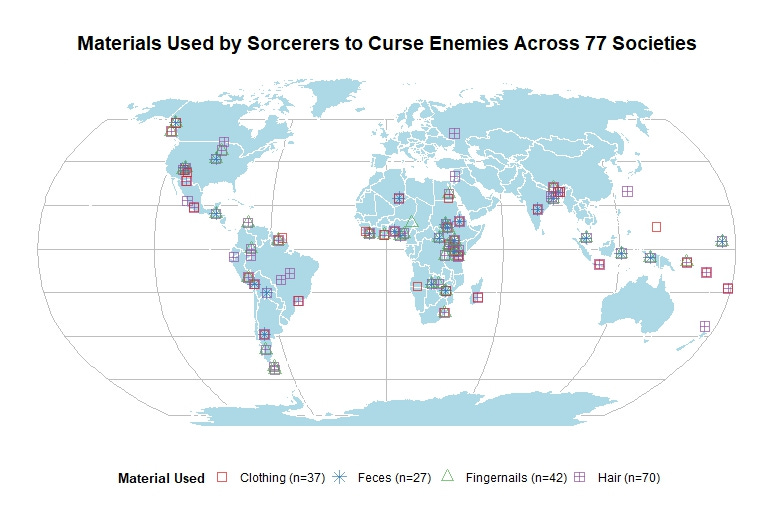

I’ve been building a dataset of black magic practices across cultures using the eHRAF World Cultures database, and currently have information from 77 societies around the world.

Overwhelmingly, the most common material a sorcerer uses to cause supernatural harm is the hair of their target.

Among the Bakairi of Brazil, “All illnesses are caused by sorcery; “there are said to be people who commission the medicine men to poison their enemies.” On the Schingú [Xingu River] one must not make an enemy of one's hairdresser.”

While hair is the most common material used, effectively any element from the target can be utilized—clothing, fingernails, feces, even dirt that was covered by their footsteps or bathed in their shadow.

Among the Lepcha of India,

To kill a particular person by sorcery it is necessary to have some of their ‘dirt’. The collective noun, used by Lepchas to indicate the exuviae, the portions of a victim's body or clothing which can be used for malicious sorcery, is mari, which means literally ‘body dirt.’ —that is hair clippings, finger nails, or clothes that have been long worn.

As a precautionary measure, clippings of hair and fingernails are often disposed of in some secret place, to avoid falling into the hands of a malicious enemy.

Among the Maori of New Zealand, “To further prevent hair being used as a medium in sorcery, the hair was laid at the tuahu, burnt, or concealed.”

An Ojibwa informant of Canada told anthropologist A. Irving Hallowell, “When my hair was cut I always burnt the part that was cut off. I was afraid that someone with power [magic] might get hold of it. If he wanted to, such a person could make me sick or even kill me.”

Among rural Egyptians, “In Egypt, as in many other countries, hair-cuttings and -combings and nail-parings are carefully kept, for if anyone else obtained possession of them he would, by their means, be able to gain an influence over, and so injure, the original owners.”

Among Maasai pastoralists of east Africa, “Hair and nail cuttings are thrown away or hidden at some distance from the kraal, so that they will not fall into the hands of an evil sorcerer, who would be able to make from them sorcery leading to a sickness for their former wearer.”

In a previous post discussing umbilical cord rituals among hunter-gatherers, I also noted examples where umbilical cords were buried, to avoid a vindictive witch cursing the new born.

The key process of many traditions of black magic, and the focus of the dataset I’m building, is that of sympathetic magic. You can harm a person by supernatural means through manipulation of some material that was once connected to them. Or, as in cases of effigies, through a symbolic representation of them.

In his work The Golden Bough, James Frazer defines sympathetic magic as having two key components: the Law of Similarity and the Law of Contagion:

First, that like produces like, or that an effect resembles its cause; and second, that things which have once been in contact with each other continue to act on each other at a distance after the physical contact has been severed.

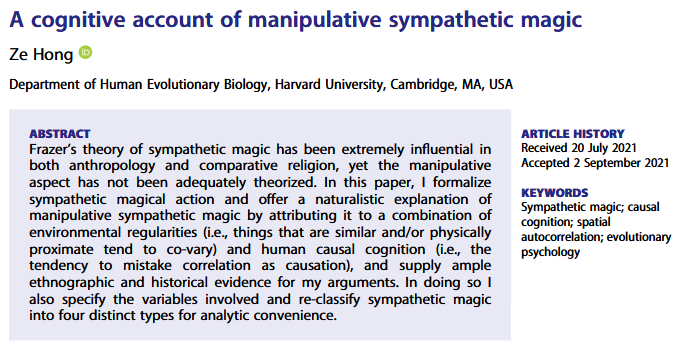

And more recently Kevin Hong has provided a formal model to help explain why practices involving sympathetic magic are such a recurrent phenomena across human societies, viewing it as “a combination of environmental regularities (i.e., things that are similar and/or physically proximate tend to co-vary) and human causal cognition (i.e., the tendency to mistake correlation as causation).”

I’m still collecting data on this, and want to do some phylogenetic analyses to see where particular beliefs and practices cluster, but the key point to understand for now is that these practices are found across independent societies all over the world, and emerge predictably due to universal facets of our evolved cognitive systems. Frazer’s recognition of the prominence of activities rooted in sympathetic magic remains a key insight. This is something evolutionary psychologists really ought to be exploring, but other than Kevin Hong’s great paper and older work by Paul Rozin it remains woefully underexplored.

In any case, even recognizing the attraction notions of sympathetic magic have on our cognitive systems, many puzzles remain. The fact that these sort of practices are so widespread and manage to persist for many generations, despite what one would assume to be frequent visible proof of failures (targets not dying after being cursed), is notable. Let’s walk through some possible explanations for why these beliefs maintain.

First, as a student socialized into the norms and perspective of Western science, the idea that you can kill someone with these supernatural methods naturally strikes me as implausible. These are not beliefs I have been enculturated into, and they run quite contrary to the sort of scientific and rationalist beliefs I have been enculturated into, so I logically am skeptical of the possibility that these beliefs and practices are widespread simply because they work as stated.

A second possibility is that a person thus cursed coincidentally dies soon after often enough for these beliefs to persist (a conflation of correlation and causation). Perhaps some sorcerers even skew the odds in their favor by actually killing their target, in secret.

While that may happen in some cases, I do think there is a more subtle middle ground between these possibilities that best explains the ubiquity and persistence of these beliefs.

Imagine you have grown up in a context where nearly everyone strongly believes these methods exist and work (this may already be the case for some readers), and you yourself have learned to believe in these ideas as well. Now imagine that, one day, you hear through gossip, and perhaps even stumbling upon your own symbolic grave or effigy, that you yourself have been cursed!

This would likely cause a great deal of anxiety and fear. Consumed with worry, you start to experience to cold sweats, and perhaps other psychosomatic symptoms. Deeply paranoid and afraid for your life, you retreat to your home to rest and hope you ‘recover’. Your compatriots witness this, convinced you will soon be dead. Desperate, you solicit the services of a shaman, who provides you with their own supernatural cure and assures you that you will be fine. Relieved, you start feeling better. Thus yourself and all observers are convinced of the reality of these beliefs—after being supernaturally cursed, you were gravely ill, and after being supernaturally cured, you recovered.

We see the clearest illustration of this in parts of Aboriginal Australia, where there are ‘wizards’ who harm people by supposedly supernaturally inserting pieces of quartz into their body, and ‘doctors’ who cure people by supposedly extracting these pieces of quartz from the patient’s body, through sleight-of-hand. See my paper ‘A Deceptive Curing Practice in Hunter-Gatherer Societies’ for more on this. It seems like psychosomatic illness induced by putative supernatural harm naturally lends itself to placebo responses induced by supernatural healing.

A prediction that follows from this perspective is that these beliefs should work best when victims believe they have been cursed. At the same time, the one doing the cursing might not want their activities to be known, as they may risk reprisal. Gossip and symbolic markers left in view of the victim then represent useful ways to spread the idea.

I plan to turn this into a preprint later on, once I’ve completed my search and done some analyses on how these practices are distributed around the world. But if you’ve found this post useful feel free to share and cite.

Other Relevant Posts: A Warrior’s Reputation, Appeasing the Dead, Cannibalism in Human Societies, Couvade, Cutting the Cord, Devotion, Gebusi Homicide and the Cultural Influence of Violence, Hostile Diffusion, People’s Vengeance on a Disagreeable Medicine Man, Symbolic Reciprocity, The Oldest Trick in the Book

Sources for this post: Link

Note: Two other cool relevant papers are Peacey et al., 2024, The cultural evolution of witchcraft beliefs and Singh, M., 2021, Magic, Explanations, and Evil.

My father-in-law is Javanese and was recently treated by a shaman extracting a needle from his skin. FIL was indeed suffering symptoms which could be psychosomatic, such as high blood pressure and nervousness. This nervousness led him to mistrust both the shaman and Western medicine. He was eventually cured for good by uncovering a voodoo doll buried in his yard, which was burned to end the long term effects of the spell.

"You have quartz cooties! Better get a cootie shot"