Homo sapiens is the Latin binomial coined by Carl Linnaeus for our species. Homo meaning man, and sapiens meaning wise. Very flattering and not altogether unreasonable, although I have often felt that man is perhaps not as wise as he would like to believe, and much of his achievements emerge through processes which he not only does not fully understand or appreciate, but actually has limited control over.

Unfortunately, my preferred alternative for Homo sapiens is already taken. Homo habilis, “handy man”— an extinct hominin species found dated from ~2.3 to 1.4 million years ago in east and south Africa.

The name was given because this species was thought to be the originator of what was previously regarded as the oldest stone-tool technology, the Oldowan industry, dated from ~2.6 to 1.5 million years ago.

Notably Oldowan tools are found in north, east, and south Africa, as well as Europe and Asia, so other hominin species beyond just Homo habilis must have also made them. And this is all further complicated by the fact that older stone tools of a different style seem to have been found dated ~3.3 million years ago at a site in Kenya.

Some species such as capuchin monkeys use stones as tools, but they don’t quite make stone tools through knapping as humans do, and as we see evidence for in the hominin archaeological materials.

One of the defining features of humans to me is not simply the making and use of tools—many possible analogies can be made in this regard, such as bird nests or chimpanzee ‘spears’ for hunting galagos—but the wholesale reliance on them for almost every aspect of survival. Tools are made and used for foraging, then wielded further to process and extract key portions of what was hunted and gathered, the substance of which is then often cooked before eating.

This is another way of saying we are a cultural species.

As important as the brain is to this process, we interact with the world with our hands. For tens of millions of years of primate evolution, many of our ancestors were at least semi-arboreal, with their hands playing an important role in moving through trees and foraging for food. In our more recent hominin ancestors after the transition to bipedalism fine motor manipulation associated with tool use became increasingly important.

The Wikipedia page for “handyman” shows a picture of this guy:

The most conspicuous aspect of this photograph to me is the belt. The handyman, limited to only two hands as all men are, creates for himself an extra set of hands through his tool belt, which hold many important items he may need during the course of his work.

While the handyman is a kind of specialist occupation in industrial societies, in hunter-gatherer societies all men generally must be handy men, and they often have their concomitant tool belts.

Among Mbuti ‘pygmies’ of Central Africa, anthropologist Colin Turnbull says that a single belt can take several weeks to make, and they they are used to “support knives, machetes, and the bundles of roots and other things that Pygmies tie to their belts while on the trail, to leave their hands and arms free.”

In early European encounters with the Hadza of East Africa it was noted that, “Normally [Hadza] men wear nothing but a skin belt round the waist, to which is attached a skin pouch for tobacco, tinder and spare arrow poison.”

Of Andaman Islanders, anthropologist A.R. Radcliffe-Brown writes that,

The only things worn by men that can be considered to have a utilitarian value are the belt of rope and the necklet of string. The belt may be a plain piece of rope, or it may be ornamented with the yellow skin of a species of Dendrobium. It serves as a receptacle in which the natives carry such things as adzes, fish, roots, or even arrows. It is the one object that is constantly worn by men.

Belts were made from the hair of deceased relatives among the Arunta of Central Australia, and they could be used for “carrying various implements and weapons, which a man sticks between the belt and his body.” Among the Tehuelche of Argentina belts were commonly used to hold arrows instead of a quiver.

Considering its common use across nomadic hunter-gatherer societies, and what it represents—as a tool to enable the carrying of more tools—the belt may be a bit of an unsung hero of human history.

Further along this vein, there is some good work on the importance of mobile containers across cultures and during human evolutionary history, although they tend to specify objects such as, “bags, baskets, pockets, slings, boxes, tubs, bins, sacks (etc., etc.)” but not belts per se.

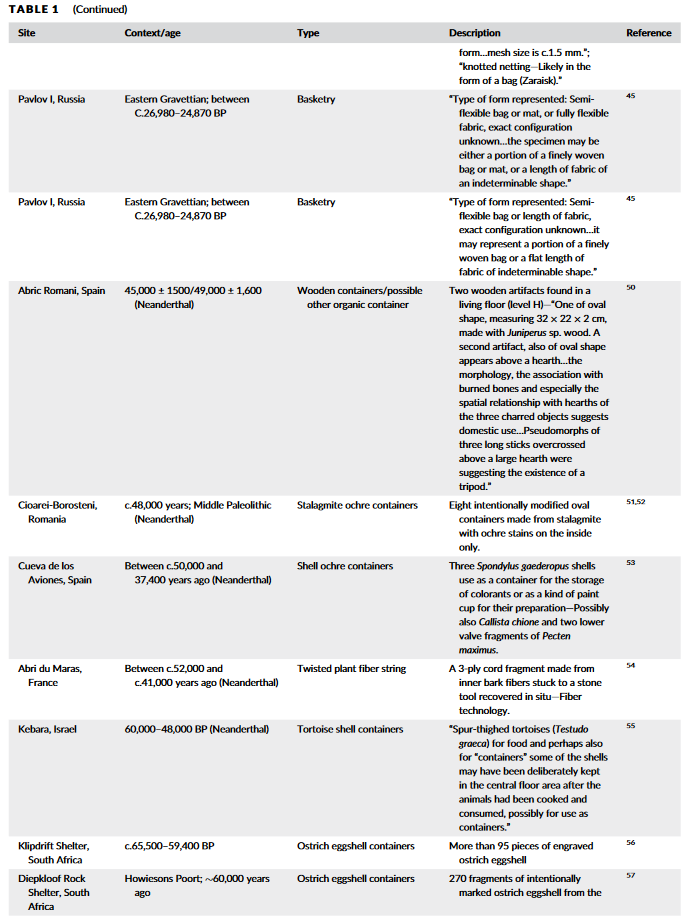

The table above provides a nice overview of the archaeological evidence for mobile containers. Note that objects such as shell containers and pottery are generally more likely to preserve than objects made of plant fibers (or human hair) such as the belts discussed above. If Homo erectus mothers were indeed using baby slings ~1.5 million years ago as some have inferred, belts may very well be of similar antiquity.

If I ever start wearing a fanny pack, I'll use this post to justify it: "yeah it's unstylish, but it's Paleo dude..."

Recently came across your work through Twitter and have found it very interesting so far.

Do you have anywhere a compiled reading list for the interested layman. Books similar to 'The Hadza' by Frank Marlowe. I'm keen to familiarise myself with the lifestyles of different hunter-gatherer groups.