Devotion

During the annual Okipa ceremony among the Mandan of the Great Plains of North America, in a display of his devotion to the Great Spirit, a young man would submit himself to tortures few human beings have ever experienced.

The Okipa was a rite closely related to the ceremony of the Sun Dance found across various Plains tribes, which generally involved rituals designed to secure the continued presence of the American bison and prepare young men for success in warriorhood.

The Mandan Medicine Lodge, where key aspects of the Okipa took place, was a secretive and sacred space. Armed sentinels guarded the entrance, with admittance given only by permission of the Conductor of Ceremonies. Women were not supposed to approach or gaze at the Lodge, nor catch even the slightest glimpse of its interior.

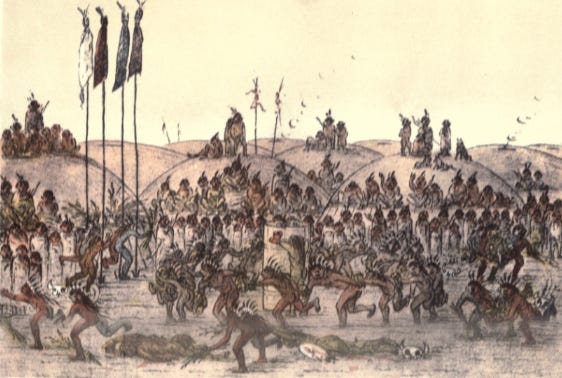

There are some key details to notice in the image above. First, all the men are nude, but covered in different colored clay as body painting, “some white, some red, some yellow, and others blue and green”. Normally, Mandan men would dress like this:

So, the body painting we see here is ceremonial, not daily attire. You can also see the men’s bull-hide shields and bows and arrows hanging on the walls.

Second, in the background you can see willow-boughs and aromatic herbs adorning the sides. The willow tree played an important role in the mythology of the Okipa rite, having been carried by a sacred bird during a key moment in their mythic history.

Third, you can see bison and human skulls arranged on the floor. As noted previously an important motive for parts of the Sun Dance and the Okipa rite was to secure the continued presence of the bison.

Finally, in the foreground you can see four sacks lying on the ground. These are made from the skin of bison’s necks into the shape of a tortoise and filled with water. Each sack has a tail of sorts made from raven’s quills, as well as a drumstick lying on top, as the sacks are beaten on as musical instruments during certain ceremonial dances. You can see two rattles nearby as well, also for use in ceremonial dances.

Explorer George Catlin, who recorded the Okipa rite and painted the illustrations in this post, tried multiple times to purchase one of the water-sacks, but was told, “they were medicine (mystery) things, and therefore could not be sold at any price.”

For the first three days of the Okipa rite, much effort was devoted to events occurring outside the Medicine Lodge, with elaborate costumed masquerades enacting the behavior and traditions of local animals, mythical creatures, and spirits.

By the middle of the fourth day, the young men in the Medicine Lodge had not eaten, drank, or slept in that time, and were ready to submit themselves to a rite of profound pain.

Two adult men were to begin inflicting the tortures. One man wields “a large knife with a sharp point and two edges, which were hacked with another knife in order to produce as much pain as possible,” and makes incisions through the flesh, while the other man slides a sharpened splint through the wounds as soon as the knife is withdrawn.

Notably, both men inflicting the tortures have their bodies painted so as to mark their own scars, demonstrating to the young men that they have gone through the same trials. The man wielding the knife also wears a mask, so that, “the young men should never know who gave them their wounds.”

George Catlin writes that,

During this painful operation, most of these young men, as they took their position to be operated upon, observing me taking notes, beckoned me to look them in the face, and sat, without the apparent change of a muscle, smiling at me whilst the knife was passing through their flesh, the ripping sound of which, and the trickling of blood over their clay-covered bodies and limbs, filled my eyes with irresistible tears.

Once the young man’s body had been prepared, with the incisions and splints passed through, “a cord of raw hide was lowered down through the top of the wigwam, and fastened to the splints on the breasts or shoulders, by which the young man was to be raised up and suspended, by men placed on the top of the lodge for the purpose.”

The image below provides some further details:

While the young men are suspended from the ceiling by splints at the breast or back, they are weighed down by bison skulls hung from splints in their arms and legs. In the young man on the left’s right-hand you can see his medicine bag, while both men have their shields hanging from splints in their arms.

What the assistants are doing with the poles is they are rotating the suspended young men, “The turning was slow at first, and gradually increased until fainting ensued, when it ceased.” Catlin writes that,

In each case these young men submitted to the knife, to the insertion of the splints, and even to being hung and lifted up, without a perceptible murmur or a groan; but when the turning commenced, they began crying in the most heartrending tones to the Great Spirit, imploring him to enable them to bear and survive the painful ordeal they were entering on. This piteous prayer, the sounds of which no imagination can ever reach, and of which I could get no translation, seemed to be an established form, ejaculated alike by all, and continued until fainting commenced, when it gradually ceased. [emphasis added]

Once the suspended young man is motionless and silent, the onlookers shout “dead! dead!”, and the men at the top of the lodge begin to lower him to the ground, while a man on the ground would remove the two splints by which the young man had been hung up, “the time of their suspension having been from fifteen to twenty minutes.” Catlin says that,

Each body lowered to the ground appeared like a loathsome and lifeless corpse. No one was allowed to offer them aid whilst they lay in this condition. They were here enjoying their inestimable privilege of voluntarily entrusting their lives to the keeping of the Great Spirit, and chose to remain there until the Great Spirit gave them strength to get up and walk away.

Once the young man had the strength to walk away, the ordeal was generally not over. The young man would go to another masked man wielding a hatchet shown in the foreground on the right of Figure 4. The young man would place his left-hand on the nearby bison skull, and thank the Great Spirit for listening to his prayers and protecting his life during the ordeal. The masked man would then strike off the little finger of the young man’s hand with the hatchet.

Sometimes, immediately after that first offering, a young man also would also offer as a sacrifice the forefinger of the same hand, leaving only the two middle fingers and thumb. Several chiefs and warriors had been known to offer the little finger of their right hand, which is considered an even greater sacrifice.

Some men, through their own volition, had gone through the Okipa tortures multiple times, with the scars on their limbs and breast to prove it.

After being suspended from the ceiling of the Lodge, and the offering of the little finger, the ordeal was still not over, for it was important that honorable scars be produced from these trials, which could not result from simply removing the splints—they must be broken out somehow, leaving a deep scar.

After six or eight young men had gone through the ordeal, they would be led out of the Medicine Lodge, “with the weights still hanging to their flesh and dragging on the ground, to undergo another and (perhaps) still more painful mode of suffering.” This portion of the ceremony is known as ‘the last race’, and takes place in front of the entire tribe.

Each tortured young man would be assigned two athletic men to him, one on either side, each adorned like so:

The painted men would wrap leather straps around the tortured young men’s wrists, and run with them as fast as they could, “the buffalo skulls and other weights still dragging on the ground as they ran, amidst the deafening shouts of the bystanders and the runners in the inner circle, who raised their voices to the highest key, to drown the cries of the poor fellows thus suffering by the violence of their tortures.”

The goal of this event from the tortured young men’s perspective was to see who could run the longest without fainting, and who could recover the fastest after doing so. The majority of them were said to have fainted before even completing half the circle, and thus would be violently dragged through the dirt, “until every weight attached to their flesh was left behind.” After each weight had been disconnected, the two painted men would flee off towards the prairie, “as if to escape the punishment that would follow the commission of a heinous crime.”

No longer burdened by the weight, once the young man gained the strength from the Great Spirit to rise again, his ordeal was over.

Despite the complexity of the rite, there are some individual motives and cultural functions we can point to as playing a role in maintaining this practice. Catlin tells us that the young men were, in some sense, engaged in a kind of competition of stoicism, seeing who can last the longest without fainting, and who can recover the quickest after doing so. Equally, while the ordeals were ongoing, the chiefs and higher status men were observing and evaluating how the young men handle the trials, in order to better decide who to appoint as war leaders or for other important posts in future conflicts.

Thus, on some levels of analysis, individual competition for prestige and group-functions related to warfare can be identified as relevant factors.

But perhaps most important and mysterious of all is the role of devotion. The young submit themselves to some of the worst tortures imaginable with the confidence that they are being encouraged and protected by a power much greater than themselves. Despite the mutilations, deaths were said to be extremely rare, with only one in recent memory according to Catlin (1867),

It was natural for me to inquire, as I did, whether any of these young men ever died in the extreme part of this ceremony, and they could tell me of but one instance within their recollection, in which case the young man was left for three days upon the ground (unapproached by his relatives or by physicians) before they were quite certain that the Great Spirit did not intend to help him away. They all seemed to speak of this, however, as an enviable fate rather than as a misfortune; for “the Great Spirit had so willed it for some special purpose, and no doubt for the young man's benefit.” [emphasis added]

It was the Great Spirit which gives the young men the power to survive these trials, and if a young man should perish in the undertaking, this was at the Great Spirit’s behest, in service of a higher purpose.

Devotion to a being, a belief, a cause—this confers a kind of power onto people, for good and for ill, which can be difficult to comprehend from the outside.

Related posts: Hostile diffusion, Ongoing series on male cults, Symbolic reciprocity.

Note: I might end up doing a follow up post or two on this, focused on the Sun Dance and how this kind of practice spread across the Great Plans. It is intriguing in the Okipa rite how some of the torturers wore masks, the shouting of “dead! dead!”, and the way the two painted men flee at the end. There seems to be a mixture of an initiation practice and a kind of human sacrifice involved in this performance. See my post Hostile diffusion for some oblique hints at how this kind of rite may have spread, I hope to touch on this aspect more concretely in the future.

Excellent summary of Catlin's observations. I had heard that this ritual was still being preformed in secret. Have you any evidence of this?

Excellent piece, the world it’s stranger than I knew. Would be interested in a follow up that taces the lineage of these rites. How widespread was the ritual in its various forms. What functions and symbols are preserved?