Hostile diffusion

"The doom reserved for enemies marches on the ones we love most." - Sophocles, Antigone, 441 BC.

Homo sapiens is a cultural species, almost entirely reliant on social learning for subsistence and survival. By necessity, we must acculturate to local context to abide and thrive. Many significant consequences follow from this.

Ideally, a person absorbs important adaptive knowledge and skills from their surrounding circumstances. Learning valuable information from parents, peers, or other community members, such as skills in foraging, social conduct, constructing tools and shelter, etc.

Of course, this is not the full extent of how humans influence, and are influenced by, each other. One underexplored phenomenon in this regard is the diffusion of cultural practices through hostile interactions.

Trophy taking in warfare offers one illustration of this. I looked into scalping practices among the North American hunter-gatherer societies in the eHRAF World Cultures database (Table 1).

I found clear evidence for scalping for 30 of the 43 societies (~70%), however it is the regional distribution that is particularly interesting.

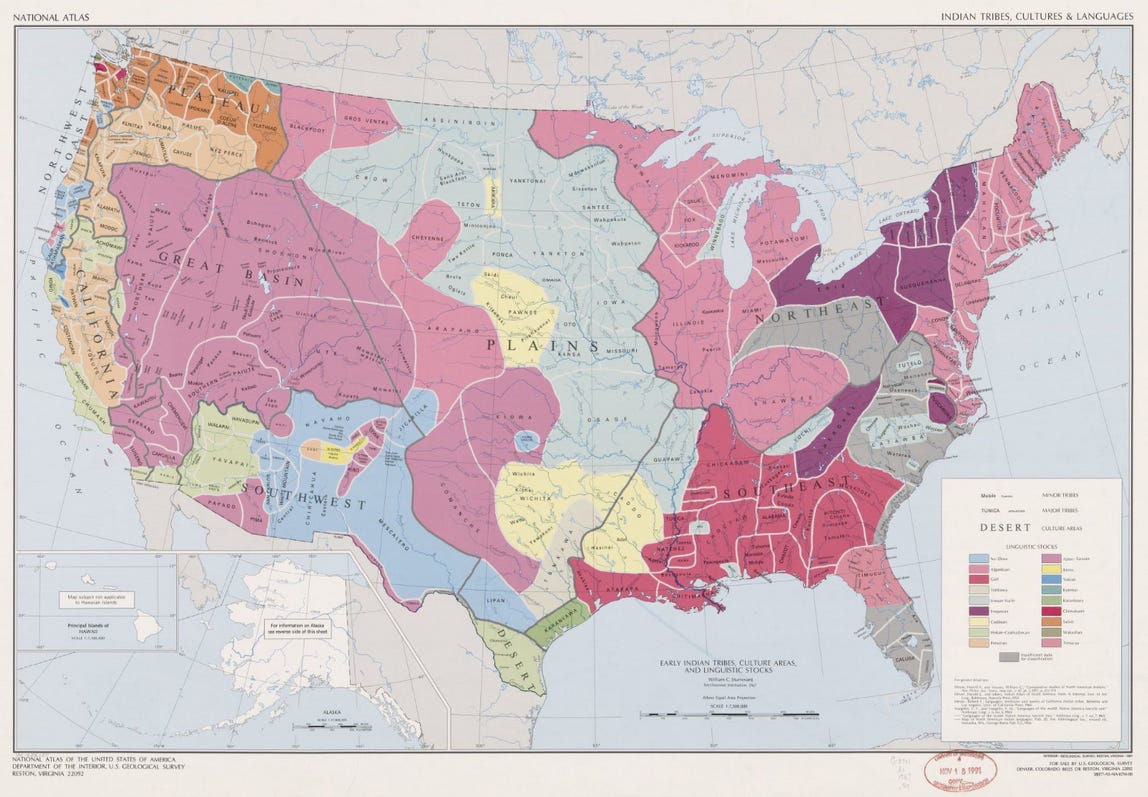

Scalping was extant, but not especially common, in the Arctic and Subarctic and along the Pacific Northwest Coast, however it was universal among the equestrian foragers further south and east across the Great Plains and the Eastern Woodlands.

Scalping seems to have a long precontact history in the Plains, as indicated by archaeological sites such as the Crow Creek Massacre along the Upper Missouri—a mass grave dated to the mid-14th century, where at least 486 individuals were buried, most of them with evidence of being scalped (and commonly other mutilations). Note however that these were agriculturalists not hunter-gatherers, and the meaning of this practice may have been quite different from the traditions discussed below.

While evidence for trophy-taking in the Americas and elsewhere around the world goes back thousands of years, the introduction of horses into parts of North America seemed to facilitate the spread and elaboration of particular scalping traditions across larger parts of the continent.

When reading descriptions of scalping, negative reciprocity between hostile communities seemed to play a strong role in motivating this behavior, even by communities apparently without much history of, or interest in, the practice. Anthropologist Marvin Opler writes that,

For example, the Mescalero feared the dead as carriers of the dreaded ghost-sickness. Normally, there would be no cult of scalping among them any more than among the Western Apache, but, indeed, this practice, rare though it was, did occur among the Mescalero and Jicarilla. However, scalping was only slightly developed and was practiced only on revengeful expeditions mostly against peoples who themselves took scalps. The reluctance to take scalps is illustrated by the fact that only a single scalp was brought back, and this was held at a pole's length [emphasis added].

In contrast to this limited use of scalping solely for revenge, various warrior cultures across the Plains had much more elaborate practices. Anthropologist Edwin Denig notes how scalping enhanced a warrior’s prestige among the Crow,

The scalps, after having been danced, were suspended from his lodge poles. His shirt, leggings, even his buffalo robe were fringed with the hair of his enemies—the last being the most distinguished mark that can be borne on the dress of a warrior, and one never used but by him who has killed as many enemies as to make a robe with their scalps.

Traditions such as this make sense in a context of frequent raiding between relatively far flung groups, with scalping representing a common conflict language to intimidate and humiliate rivals. Anthropologist Alfred Kroeber provides a case of Crow people themselves being scalped by Gros Ventre men, described by a man named Bull-Robe:

The Gros Ventre shot a Crow, and I ran forward and took his gun. I was jumping about constantly, so much did they shoot at me. The Crow charged me, but were not brave enough to drive me back. Two of our men came to me, and we stood below a little ridge. The Crow women shouted, and some of them cried for the dead; but it did them no good. About sunset they stopped fighting, and retreated. Then we got up, put the scalps on a pole, and danced, taunting the Crow. All the Crow women and some of the men cried [emphasis added].

Beyond the taking of trophies, there are other ways cultural beliefs and practices may spread through violence. Anthropologist Franz Boas, in describing the social organization and secret societies of the Kwakiutl of the Northwest Coast, writes that, “Names and all the privileges connected with them may be obtained…by killing the owner of the name, either in war or by murder. The slayer has then the right to put his own successor in the place of his killed enemy. In this manner names and customs have often spread from tribe to tribe.”

Among the Asmat of New Guinea, somewhat similar notions are taken even further in men’s headhunting practices, where they use the heads taken from enemy communities to initiate their younger male relatives,

The informants emphasized repeatedly that the initiate is smeared with the ash of the burnt hair and with the blood of the victim. This is explained by the fact that the initiate assumes the name of the victim. This identity between victim and initiate will later prove very useful. When meeting the initiate, even after many years, relatives of the murdered person will always call him by his assumed name, the victim’s name, and treat him as their relative. They dance and sing for him and give him presents. It is strictly forbidden to kill people from other villages who, because of their ritual names, are related to one’s village. These people are often chosen to be negotiators [emphasis added].

Anthropologist Donald Tuzin described how homicide masks worn in the men’s secret society among the Ilahita Arapesh of New Guinea could spread through enemy communities after its owner committed a killing,

the killer might have cut the trappings of the mask and fled with it to a nearby enemy village. The nature of his mission would have assured him safe passage into their territory, where he could make contact with someone—a kinsman, perhaps, or other acquaintance—who would offer to take custody of the mask, since what the hangamu'w had done was surely a favor to the enemy. The mask remained with the enemy either until it killed again and fled to yet another village (or possibly back to its home village), or until it was repatriated at the request of the true owner. In the latter event a payment of yams and park was given as a kind of ransom to those who returned it [emphasis added].

Captives taken in war can also be agents of change and cultural transmission in their new society. Anthropologist Catherine Cameron writes that,

In some instances, captives from distant or exotic places, especially those with special knowledge or skills, could engender more positive, although likely guarded, attitudes. Helms (1988, 1998) has documented the power that knowledge of distant places can impart to travelers and others (see also Kristiansen and Larssen 2005). This suggests that captives could use knowledge of their natal society or of other groups to which they had been traded to negotiate a position of influence in captor society. Captives could bring novel curing methods, medicinal treatments, religious rituals, or cultural practices (DeBoer 2008). Such special knowledge could make them intriguing but also dangerous individuals. Captives held by the most prominent members of society might have been in an especially good position to transmit their natal culture. For example, in the West African kingdom of Dahomey, Bay (1983:340–341) reports that women slaves served as ministers of state, counselors, soldiers or commanders, provincial governors, and trading agents as well as favored wives. In these positions, they would likely have significantly enhanced abilities to transmit aspects of their natal culture. Bay (1983:347) emphasizes that female slaves were an important channel of cross-cultural influence, providing accounts of a female slave, held by a king, who introduced new deities into the pantheon of local gods and others who transmitted other religious practices, including Islam. Similarly, Lenski (2008) documents the role of captives in the spread of Christianity among the Germanic tribes during the first few centuries of the Current Era [emphasis added].

Notably, for trophy taking in war—and the practice of scalping in particular—the dynamic of violence and negative reciprocity appear central to its spread, however a captive might be adopted into a group and transmit cultural practices in ways not too dissimilar from any other member of the community. The Asmat headhunting practices discussed further above offer an interesting middle ground, where killings between villages are used to initiate young men and establish certain kinds of peaceable relations between otherwise hostile communities.

I think i remember reading there was some scalping by white men in retaliation for Indian raids in Texas at some points, that seems like another interesting example.

great info, thanks! the description of how Crow warriors used scalps to enhance prestige is remarkably similar to the way Herodotus described the use of scalps by Scythian warriors—also an equestrian plains people. you draw a distinction between negative reciprocity and prestige as a motivation for the taking and treatment of scalps. is there something inherently different about plains equestrian culture that prefers one over the other?