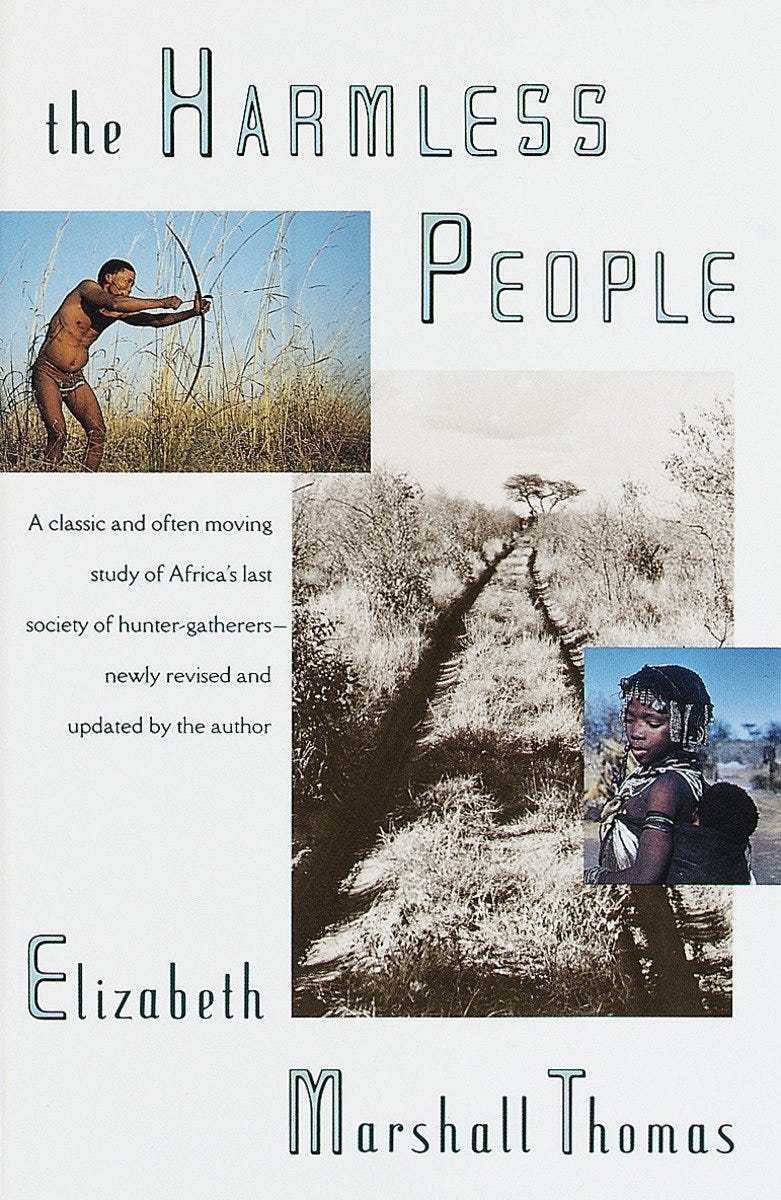

This post recounts events described in the book The Harmless People (1958, 1989) by Elizabeth Marshall Thomas.

Among the Bushmen of Nyae Nyae in Namibia during the 1950’s, the man known as Short Kwi was famous for his hunting prowess. Tales were told of his great achievements in the chase—the time he killed an eland, a wild pig, and a wildebeest in a single day; the time he killed four wildebeest in a large herd—his exploits were legendary.

He was said to be a relentless pursuer who almost never lost an animal. He could pick up a cold trail even over stones. He deduced subtle clues from fallen leaves, such as whether they had been disarrayed by the wind or the movements of his prey. The meat from his pursuits was never wasted, as it was shared liberally and dried to last weeks.

He had encyclopedic knowledge of the animals in his environment—from the smallest mice to the largest antelope, he knew by heart their habits and where they could be found. Elizabeth Marshall Thomas writes that, “He knew every bush and stone in the area of thousands of square miles that he ranged over, and he lived for hunting.”

Short Kwi would sometimes hunt with others, although he mostly hunted alone. His family lived fairly independently in the bush, with just his wife, young daughter, and mother-in-law with him.

He was a small, slender man, even shorter than his wife, and spent much of his time hunting, his passion and occupation. “He would hunt on and on and when word would reach the large band of his wife’s family that he had killed, the band would go out to where the animal was, dry the meat, and eat it.”

While the Bushman practice of ‘shaming the meat’ to prevent an effective hunter from getting a big head is well known, with Short Kwi, “his great ability set him so far apart from ordinary mortals that for once the Bushmen forgot their jealousy and agreed that he was the best hunter the Kalahari had ever known.”

It was a common custom among the Bushmen for the men to cut strips of antelope skin from the forehead of their prey and make them into bracelets for their wives. Short Kwi’s wife and daughter had their arms covered in dozens of these bracelets, demonstrating his hunting skill, although Short Kwi himself wore no ornaments.

Short Kwi was brave, and he was careful.

Once, Short Kwi and two other hunters were tracking a wildebeest that one of the hunters had shot. They found it lying down, still living, surrounded by a pride of about twenty to thirty lions, having apparently decided to obtain this relatively easy prey for themselves. The wildebeest was struggling effectively however, protecting itself from the lions’ attacks with its horns.

The bushmen came across this scene and slowly approached. “We know you are strong, Big Lions, we know you are brave, but this meat is ours and you must give it back to us,” they said. “Great Lions, Old Lions, this meat belongs to us,” they spoke respectfully, but threw little stones and clods of dirt at the lions. The lions began to back away and eventually left the scene.

The wildebeest was still active. As it tried to get to its feet and fight off the men, Short Kwi threw a spear which landed strong into the wildebeest’s neck. The wildebeest continued to struggle with the spear lodged in its neck. Each time one of the men tried to grab the spear, the beast would lunge its horns towards him, forcing him to quickly jump away.

Finally, as one of the men distracted the wildebeest from the front, Short Kwi rushed the wildebeest and extracted the spear while passing over its back. John Marshall, an anthropologist who was there at the time, asked Short Kwi to perform the same maneuver again for a picture. However, Short Kwi declined. “This time he will remember,” Short Kwi said, before killing the bull by throwing the spear again into its throat.

One day, though, Short Kwi’s legendary attentiveness failed him. Without seeing it, he stepped on the tail of a puff adder, which rose up and bit him just below the knee. “His misfortune was regarded as a horrible accident and it was felt that the spirits of the dead were to blame,” Thomas writes.

In the bush there is little opportunity for medical care. Thomas writes that after the bite, “Short Kwi had been sick a year and had not died, but the flesh had gone from the calf of his leg, said Gao, the skin had gone from his foot, his foot was curled and the bones were showing.” Thomas was visiting Short Kwi’s community at this time and, offered to take him to a doctor for treatment.

One night, before they had left for the doctor, part of Short Kwi’s leg fell off,

When the calf had fallen off, Short Kwi was crying and biting his hand and his wife was crying, and Toma and Gao Feet stood beside him for a minute looking, the expression on their faces as dark as night. Then they picked up the leg and carried it away to the veld, where they buried it in a hole, exactly as if it were a person, they were so sad.

Soon after this, Short Kwi was brought by truck to a hospital, where the rest of the gangrenous flesh was removed, and he was fitted with a peg leg. When they returned, Thomas writes that, “We told all this to the Bushmen, but they were not really pleased. The miracle which they had perhaps expected had not taken place, for Short Kwi was still a cripple, and he always would be.”

Elizabeth Marshall Thomas would leave shortly after this, returning around thirty years later in 1987. On this trip she would learn of Short Kwi’s fate.

Short Kwi managed to overcome his disability, walking with his peg leg throughout the bush wherever he wanted. He eventually brought his family to live at the town of Tsumkwe. At Tsumkwe, Short Kwi’s daughter would grow up to marry a highly paid, hard-drinking soldier.

One night, while blackout drunk, the soldier stabbed Short Kwi to death. They had no obvious quarrel, and in the morning the soldier was mystified to learn of what he had done. Thomas thus concludes her account of Short Kwi’s life, writing that,

So all of Short Kwi’s courage, endurance, intelligence, ability, and ingenuity amounted to nothing. He lies in a shallow, trash-strewn grave on the outskirts of Tsumkwe. His widow moved to Gautscha, her traditional home. Later, in remorse, the son-in-law tried to kill himself by the method many people favor nowadays—he stabbed himself in the arm with a poison arrow. People rushed him to the infirmary, where a doctor saved his life by cutting off his arm. Now he, like his father-in-law, is an amputee.

Postface

It is often emphasized that a main driver in the massive increase in life expectancy over time is through improvements in infant and child mortality. Keep in mind, however, that people in contemporary industrialized societies also tend to have less exposure to many natural hazards throughout the lifespan—such as the snake bite Short Kwi experienced—than people across most ‘preindustrial’, and particularly hunter-gatherer, societies. Among the Aché hunter-gatherers of Paraguay for example, snakebite made up 6% of all deaths, and 14% of all adult male deaths in particular.

Note further the devastating social effects the introduction of strong alcohol can have on ‘traditional’ populations. The Epilogue of The Harmless People contains multiple other sad accounts of violence under the influence of excessive alcohol consumption that Elizabeth Marshall Thomas learned of when she returned in 1987.

> So all of Short Kwi’s courage, endurance, intelligence, ability, and ingenuity amounted to nothing.

I find this assessment almost breathtakingly offensive. He was a hero among his people in his prime and certainly fed many with his hunting prowess. That his life ended in tragedy does not obviate its value nor the significance of his earlier accomplishments. Heck, simply enduring an injury like his and finding a way to continue productively despite diminished capacity is worthy of admiration.

"So all of Short Kwi...amounted to nothing?" That is a blindingly ignorant assessment. Her own view on death is that we return to molecules knowing nothing. Her powers of observation and recall are impressive but her summation and conclusions are not.