Underestimating Social Complexity Among Hunter-Gatherers

Anthropologist Robin Dunbar has a recent paper arguing that as group size increases—particularly with the historical transition to larger and more sedentary agricultural societies—additional social institutions are required to manage the challenges of group living. Dunbar compares 11 hunter-gatherer societies with 14 village-based cultivators and predictably finds that the larger population cultivators have more social institutions in terms of charismatic leaders, between-group coalitions, men’s clubs, and so on, than the hunter-gatherers do.

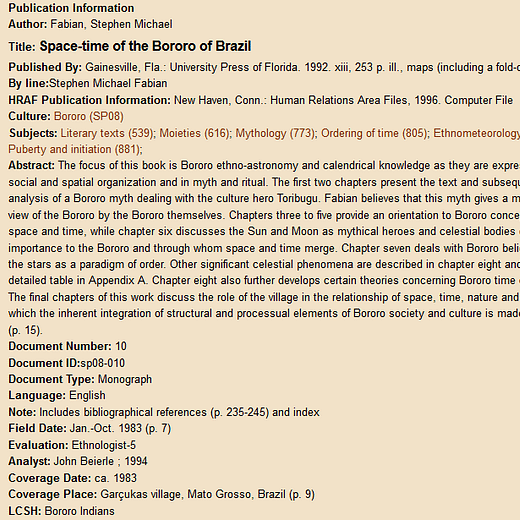

After reading the paper, I did what I always do after reading a paper like this—I checked the supplement to see if the coding decisions were reported so I could evaluate them for myself. Thankfully they were very clearly and transparently reported (this is admirable, not common enough, and worthy of praise). Here are the codes for the hunter-gatherer societies in the sample:

And here is how the various categories were defined:

Because I have pretty good familiarity with the ethnographic evidence for most of these groups, it seemed clear to me that many of these social institutions are significantly underestimated across these hunter-gatherer societies. Let’s go through a few of these societies and note some of the key omissions.

Based on the coding decisions, the Ache are claimed to have none of these social institutions, and the cited source in the supplement is Hill & Hurtado’s 1996 book Ache Life History. By my read of that source however, the Ache should instead be coded as having at least “between-group links”, “men’s clubs”, “male status”, and “marital services”.

Regarding the first three, evidence comes from the Ache institution of club fights. Hill and Hurtado write,

Organized club fights were often called to exact revenge for an event that could be “blamed” on some individual or individuals. If children were captured or killed by Paraguayans, or killed in any freak accident (such as lightning striking, or a tree falling), a relative, a man who had provided the essence, or a godparent of the child might call for a club fight in order to avenge the child’s death. The death of an important adult very often led to an organized club fight. In addition, older and powerful adult males would sometimes call club fights “just because they wanted/liked to.” Informants admit that in addition to calling club fights in order to avenge the victim of an accident, club fighting was organized by big men so that each man could “display one’s strength … to show how strong we are.” (Hill & Hurtado, pg 71). [emphasis added]

Note that these meetings could involve over a dozen bands with hundreds of people coming together,

In order to bring together the 10–15 bands that might be scattered as far as 100 km apart, runners were sent out with the message that a club fight was to be held at some location. Not all bands attended, and some purposely avoided the event. Nevertheless, usually close to half the Northern Ache group would attend a single “organized” club fight. The camp would sometimes grow to include 300–400 people. (Hill & Hurtado, pg 71). [emphasis added]

Somewhat in keeping with the logic of Dunbar’s paper, it’s clear that these club fights, despite being quite violent, were a mechanism of social control to stamp down on other forms of within-group violence between males. Hill and Hurtado write,

In-group killings among adults account for 10% of all adult female deaths and 11% of the adult male deaths. Club fights were the single most important cause, accounting for about 8% of the deaths to males over fifteen years of age. Only one person (a teenage boy) in the twentieth-century population was shot with an arrow. This is in keeping with a strongly demonstrated aversion to uncontrolled in-group violence. Although the Ache killed all outsiders on sight before peaceful contact, club fights were the only sanctioned form of violence between men within the population itself. Other adult deaths from conspecific members of the Ache population included being buried alive because of old age or sickness, and being left behind to die (because of illness or blindness). (Hill & Hurtado, pg 164). [emphasis added]

Dunbar surprisingly writes in his paper that he, “deliberately avoided institutions that are mechanisms of control (e.g. laws, punishments, policing, or mechanisms for resolving disputes such as duels), since these tend to be associated with much larger scale societies.” However, as I showed in a previous paper, most hunter-gatherer societies actually do have dueling traditions. I don’t understand where Dunbar got the claim that duels “tend to be associated with much larger scale societies”, as nothing appears cited to support it and I don’t think it’s true. See my Works in Progress article ‘Why we duel’ for a summary.

Regarding “marital services”, Hill & Hurtado write that, “Almost all new marriages are characterized by matrilocal residence and behavior that might be called bride-service,” (pg 235) and they also favorably quote at length a description from a missionary in the 1600’s,

The one who is fortunate enough that a daughter is born to him, is very careful in raising her, because through her he will become the head [leader] of others; being the inviolate law of the guayaguis that a son-in-law must follow his father in law, and become part of his family, because among them they have no chiefs, only that the brothers and sons-in-law get together in a group and recognize their father or father-in-law as the leader; but the power that he enjoys over others is very limited, since each lives according to his own whims. (quoted in Hill & Hurtado, pg 46). [emphasis added]

The ostensible lack of marital services across Dunbar’s sample is very difficult to understand since bride service is clearly very common across hunter-gatherer societies, even just for the societies and sources Dunbar covers here.

Dunbar’s source for the Hadza is Marlowe’s 2010 book on them, and in that book Marlowe writes that, “Hadza say it is best to live with the wife’s mother in the beginning, during the birth of the first few children, and then later to live with the husband’s mother. This is a common view among foragers, many of whom expect a new husband to perform bride-service for his wife’s parents (Marlowe 2004c) [emphasis added].” The source Marlowe cites there is his own 2004 paper in Current Anthropology, “Marital Residence among Foragers”. As the table from that paper below shows, most hunter-gatherers have some form of “marital services”, particularly bride service (see the column “Marriage Model/Alternate”).

Dunbar claims no “marital services” among the Dobe !Kung, and his source is Richard Lee’s 1979 book The !Kung San: men, women, and work in a foraging society, yet Lee clearly notes bride service among them, writing that,

Traditionally, the prime characteristics parents of a girl sought in a son-in-law were proved hunting ability and a willingness to live with his in-laws and provide meat for them for a period of years. This period of "bride service" is common among the Dobe !Kung and was even more frequent in occurrence among the Nyae Nyae !Kung during the 1950s. (Lee, pg 240).

The sourcing Dunbar gives for some societies is also inadequate. The only source given for the Tiwi of of Australia is a single 13 page paper, which is odd since multiple excellent books from different authors have been written about them.

Anthropologist Jane Goodale describes bride service among the Tiwi in her 1971 book Tiwi Wives, writing that the son-in-law,

must supply her with all she demands in service or goods, including today clothes, tobacco, money, and the like. If he is lucky to have a mother-in-law who gives him two or more wives, the payments do not increase, for the simple reason that there is initially no limit to what he must do for his ambrinua [mother-in-law] in return for only one daughter. (Goodale, pg 52)

I also have unpublished data on 21 hunter-gatherer societies (reanalyzing Fry & Soderberg’s 2013 sample) and I found that 15 of them practice some form of bride service. The only overlap between that and Dunbar’s sample are 3 societies: the !Kung, the Hadza, and the Tiwi, and by my read all 3 of them very clearly have marital services. Anthropologist James Woodburn writes in his chapter on the Hadza in the 1968 volume Man the Hunter that, “Long strings of bridewealth beads should be, and usually are, given by the bridegroom to his parents-in-law. They are taken and worn by the mother-in-law around her waist. Thereafter, throughout his life of the marriage, the husband should keep his wife and mother-in-law supplied with meat and with trade goods.” (pg 108)

What I found most frustrating is the supposed lack of “men’s clubs” across these societies, with only the Blackfoot coded as having them. I have been covering the topic of men’s cults across small-scale societies for years, so it was clear to me immediately that this is very mistaken. As I found in my previous paper on disguises in hunter-gatherer societies,

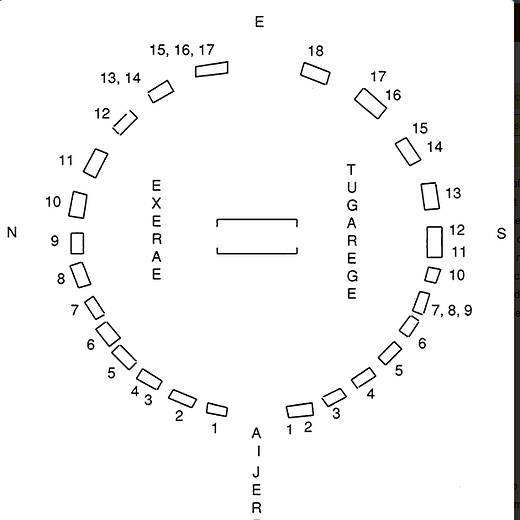

Seemingly the most elaborate disguises and strategies of deception in this sample are employed to mimic otherworldly entities in ritual or cult contexts (detailed in Table S2). Four of the 10 societies (Arunta, Bororo, Mbuti, and Ona) have cult practices in which adult males impersonate mythical beings for purposes of deceiving uninitiated women and children, and for three of these societies (Arunta, Bororo, Mbuti) musical instruments are used in secret to mimic the voices of these spirits and add to the credibility of the illusion. In each of these societies the men have secret feasts forbidden to uninitiated women and children (Colbacchini, 1942:286; Gusinde, 1931:1512; Murdock, 1934:35; Spencer & Gillen, 1927:298; Turnbull, 1962:184), often with the claim that the food is consumed by the spirits. [emphasis added]

[And note I was only looking at disguises there, not “men’s clubs” more broadly, which would have been even more common].

To be fair, the societies across our samples are mostly non-overlapping, with the only one in common being the Blackfoot, so hypothetically it could be differences in our samples that led to different results. Except, that’s not the case and again the problem is with the codes. Marlowe discusses the Hadza tradition of Epeme feasts, which is the men’s secret ritual complex, writing that,

Epeme refers to the whole complex of manhood and hunting, but also to the new moon and the relationship between the sexes (Woodburn 1964). Fully adult men are referred to as elati, or epeme men. When a male is in his early 20s and kills a big-game animal, he becomes an epeme or fully adult man. Certain parts of all larger game animals can be eaten by the epeme men only. Not only can females and sub-adult males not eat the meat, they cannot even see the men eat this meat or, it is said, they could die or get ill or suffer any number of misfortunes.

Tiwi boys of Australia spend years, from their mid-teens to early-twenties, out in the bush away from women, going through ritual stages under the guidance of older men (Hart & Pilling 1960, pgs 93-94).

The Murgin of Australia are claimed to have no “between-group links” or “between-group alliances” but the source Dunbar cites, Kinship and Conflict (1965) by Hiatt, notes they have ‘totems’ which can cut across land-owning units and involve monopolization of certain symbols and be a source of support in fighting (Hiatt, pg 14). The men also had secret rituals and could gain status through participation and knowledge. Hiatt writes that, “Secret ceremonies allowed more scope for individual enterprise; some men, not necessarily those advanced in age, achieved recognition for their ability to direct certain rituals and their expert knowledge of the associated mythology.” (Hiatt, pg 146).

The Anbarra of Australia also had secret male rituals. The source Dunbar cites is Betty Meehan’s 1975 dissertation Shell Bed to Shell Midden. Meehan writes that, “The ceremonial ground was situated a short distance to the southwest from the main camp site and there, all the secret ritual was performed and the novices (wori) were kept in seclusion away from all females and uninitiated males.” (pg 52) Meehan notes that women’s foraging mobility was actually restricted somewhat because they were not allowed to go near the men’s ceremonial grounds.

The source for the Agta of the Phillipines is a single 30 page paper, Minter (2017) Mobility and Sedentarization among the Philippine Agta, Senri Ethnological Studies, mostly focused on postcolonial changes. There isn’t sufficient information there to draw conclusions about the presence or absence of any of the coded social institutions.

The sources for the Waorani of South America are two relatively brief papers focused on specific topics, Macfarlan et al. (2018). Bands of brothers and in-laws: Waorani warfare, marriage and alliance formation, Proceedings of the Royal Society, and Rival (1993). The growth of family trees: understanding Huaorani perceptions of the forest, Man. These are clearly not sufficient to give a substantial account of structural traits across this society, however both sources discuss marriage alliances, and the latter notes the presence of drinking ceremonies, feasts, and chiefs, which seems inconsistent with the codes.

Describing the Waorani as ‘hunter-gatherers’ is also debatable (not wrong necessarily, but debatable) since they practice a significant amount of cultivation1, which is the source of their feasting, despite “within-group bonding rituals” being erroneously coded as absent in the Dunbar paper. Same goes for the Ayoreo of South America, who also have feasts with some cultivated products, but are coded as lacking “within-group bonding rituals”.

Overall the logic that human social living requiring various institutions to navigate conflicts of interests rings true, but hunter-gatherer societies are far more complex than they’re given credit for in Dunbar’s paper. I don’t think their social institutions are even necessarily less complex than those of agricultural societies generally, and certainly the evidence provided in the paper does not show that. I have not gone through every single one of the codes, but it should be clear from the above that many of the codes are mistaken and they should not be taken at face value.

This critique isn’t really unique to Dunbar’s paper though, my main conclusion is actually this: you cannot trust other people’s codes. If all you know about hunter-gatherer societies is other people’s generalizations about them, you don’t actually know much about them. You have to read the underlying ethnography for yourself and reach your own conclusions. Obviously that takes a lot more time than reading a secondary source that purports to sum them up and taking their claims at face value, but that’s just how it goes if you want to have an accurate understanding.

Related posts: Why we duel, Ongoing series on male cults, Women’s secrets, The Oldest Trick in the Book (charismatic leaders among hunter-gatherers), Diss Songs (conflict resolution among hunter-gatherers), Some Uses of Musical Instruments in Hunter-Gatherer Societies.

As Raymond Hames notes in the comments, the Waorani get a pretty substantial amount of their calories through horticulture, so coding them as ‘hunter-gatherers’ probably is in fact more “wrong” than “debatable”, I was perhaps overly charitable there.

"Always read backwards from secondary sources to primary sources and then write forwards from primary to secondary." A wise historian told me this once and it probably works for anthropology, too.

Hello, Will,

Do not know why you suggest whether the Waorani are hunter-gatherers when MacFarlan et al. say "The Waorani are an indigenous Ecuadorian, lowland Amazonian population of approximately 2000 people today. At first peaceful contact (1958), they subsisted on manioc, banana and peach palm cultivation supplemented by hunting.

My read of the extensive work of Beckerman (co-authored with the MacFarlan reference above) as well and Larrick and many others describe them as rather standard Amazonia horticulturalists who also do a great deal of foraging but whose diet is probably calorically around 60% or more from horticulture.