Research over the last few years has demonstrated some important patterns of music use across societies. Music appears to be universal across cultures, is used in a diverse array of contexts, and people (internet users across countries at least) seem to be pretty good at making accurate inferences about some song functions (dance songs, lullabies, healing songs, and love songs) when hearing music from unfamiliar societies, even just from brief snippets.

Based on findings such as these, I started looking at the use of musical instruments in hunter-gatherer societies with two particular predictions in mind: 1) people should use music to fulfill multiple communicative functions across societies, such as for making an announcement or offering an invitation. If people can rapidly and reliably infer certain conventional meanings from music, then musical instruments ought to also be useful for producing simple messages to quickly convey information across distances and to numerous people at once.

However, 2) if people reliably pick up certain cues from music, then this communicative system should also be vulnerable to exploitation. If I know what information you derive from a certain sequence of notes, I might be able to use this to deceive you, like a bad horror movie using ominous music to create tension despite nothing frightening happening on screen.

I searched eHRAF for four particular musical instruments (trumpets, flutes, whistles, and bullroarers) across societies defined as at least ‘primarily hunter-gatherer’ (>56% of subsistence from wild resources). I looked specifically for a clearly described or conveyed communicative function, but did not include more general contexts (such as dancing, entertainment, or healing). Table 1 covers common functions of these four musical instruments across the 42 hunter-gatherer societies where I found evidence.

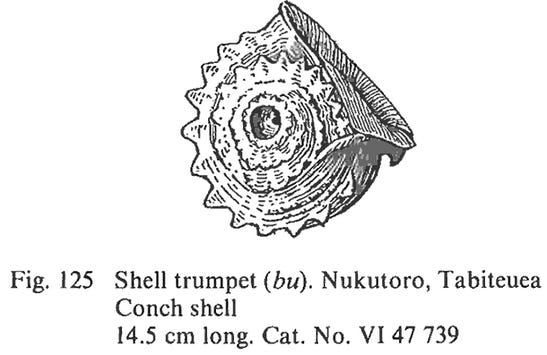

As you can see, certain practices appear pretty widespread, such as the use of trumpets or whistles to signal a greeting, invitation, or announcement. The Warao of Venezuela signal their return to the settlement after a successful crab-hunting expedition by blowing a shell trumpet. Among the Bau Fijians the death of a chief was announced by shell trumpet. For certain ceremonies among the Xavante of Brazil, leaders would blow gourd whistles to signal the beginning of the proceedings.

I didn’t include this in Table 1 because it’s not a traditional case—and it didn’t really fit the category—but anthropologist Frederica de Languna offers an interesting post-colonial account among the Tlingit of Alaska, describing how, “The Tcicqedi and Galyix-Kagwantan [clans] sang a Copper River song when coming on the steamer to the Kwackqwan potlatch at Yakutat in 1905. The steamer’s whistle was used as a signal to start and stop the song. [emphasis added]”

Trumpets and whistles are also commonly used to signal an attack, although it’s not always clear whether it’s a way of organizing the attackers, or to inspire fear and panic in the enemy, or both. Among the Maori of New Zealand a shell trumpet was used, “for signalling the approach of enemies, the return of a raiding party, and by a commanding chief for directing or rallying his force during a fight.” The Abipón of Paraguay and Argentina engaged in “surprise attacks accompanied by the loud blowing of trumpets and whistles to disorient their foe.” Among the Creek of Oklahoma whistles were used by leaders in pitched battles as the final signal for engagement.

The use of flutes in courting is quite interesting, although in this sample the practice appears to have been exclusive to societies across the North American Plains or those that had contact with them. These love flutes seem to effectively represent a single tradition that diffused across one region, as opposed to the clearer examples of independent invention across regions we have for the other categories. Anthropologist Mark Awakuni-Swetland writes that among the Omaha of Nebraska,

Love songs played on a flute from afar were one method of indicating an interest in a girl. Marriage was often by elopement so that the girl could escape from the claims of her potential marriage partners. After escaping to the home of one of the boy’s relatives, the young couple would return a few days later to the girl’s parents’ home. The boy’s relative presented gifts to the girl’s relatives. If they were accepted, it signaled recognition of the marriage.

Regarding the use of musical instruments for deceptive purposes, trumpets and whistles are sometimes used in hunting mimicry, although this task is more commonly accomplished vocally across societies rather than with the aid of an instrument.

The use of bullroarers, flutes, trumpets, and whistles to impersonate spirit sounds is notable. These instruments are commonly meant to convey the voices of spirit beings or mythical animals, and they may double as a signal for the uninitiated women and children to hide away in their huts while the men do their rituals or have their feasts. Among the Mbuti of Central Africa the molimo trumpet gives voice to a sacred animal. Anthropologist Colin Turnbull writes that,

Usually the trumpet is heard at about the time the band normally retires for the night. The women in any case have been aware of whatever crisis is the occasion for the meeting and are prepared for it. On hearing the trumpet, they take their children and shut themselves in their huts. None will come out, even to cross the clearing. The men sit close together around one of the fires. As they sing, the molimo trumpet echoes their song, sometimes coming close, sometimes going far away into the forest.

As I discussed previously in my paper on disguises, across various hunter-gatherer societies, “musical instruments are used in secret to mimic the voices of the spirits and add to the credibility of the illusion. [Among the Arunta of Autralia, Bororo of Brazil, and Mbuti of Central Africa] men have secret feasts forbidden to uninitiated women and children, often with the claim that the food is consumed by the spirits.” Before the molimo ceremonies a basket is hung up in a prominent place with offerings for the molimo animal, which the women are expected to keep filled.

As Margaret Mead wrote of the Arapesh horticulturalists of New Guinea, “The secret of the House Tambaran and the sacred flutes…resolves itself into the way the men keep meat away from the women by saying that the monster eats it and then secretly consuming it themselves. The flutes the men blow to scare the women away while they hide the meat.”

Anthropologist Ian Keen described three days of ceremonies among the Yolngu of Australia [not included on eHRAF], writing that,

Each evening a rhythmical banging noise originating on the salt plain behind the camps along the beach resonated through the settlement. The men told the women and children that the spirits were making this noise by stamping on the ground with one foot. While this was going on Yirritja men…walked through the camps collecting flour, tobacco, sugar, etc. 'to feed the wangarr [ancestors] and the spirits'...

How the ‘rhythmical banging noise’ was achieved is not described, as far as I can tell. Keen says earlier in the work that, “it would be a breach of my obligations to [Yolngu men] if I were to publish religious secrets in a work of this kind. I have omitted all but the barest indication of what goes on in the men's secret-ceremony grounds,” so the procedures involved in cases like this among the Yolngu and potentially other societies may not always be mentioned or known to the ethnographer.

See my previous piece on bullroarers, which seems to be an instrument particularly well suited for impersonation of spirits (and weather manipulation).

Overall musical instruments appear to be commonly used across hunter-gatherer societies to convey certain types of simple messages, such as an announcement or attack signal, as well as being used deceptively to impersonate animals and spirits.

very interesting. the article did not mention percussion instruments, and i wonder whether some percussion instruments would be the earliest musical instruments used, such as different primitive drums and and shakers. Percussive patterns could have been used as some sort of a primitive morse code for communication, long before the capability of using other instruments and vocal communication evolved.

interesting how consistent the pattern seems to be across societies. i'm curious whether the women are genuinely naive to the impersonation of spirit voices or the disappearance of meat, etc, or if there is any indication that they are just performing their designated role in some ritual drama.