[Note: If you are concerned about spoilers, I recommend seeing The Northman first, however I do not spoil anything here that wasn’t already revealed in the trailer or in scenes that were released online before the film came out.]

One of my favorite books is Headhunting and the Body in Iron Age Europe (2012) by archaeologist Ian Armit.

An important contribution this work makes is to connect the cultural practices of historical European societies to those of other ‘traditional’ societies from all over the world. Over the course of his work on Late Bronze and Iron Age archaeological sites in Europe, Armit found that ethnographic descriptions from societies in different parts of the world were essential for understanding the historical European cultural materials that have been found.

Armit writes for example in an earlier paper that, “In widely disparate ethnographic contexts, on at least three continents, the taking of heads appears to have become associated with notions of fertility (of humans, crops and animals),” and notes that “Evidence for headhunting is also common in prehistoric Europe.”

Armit & Ginn (2007) provide a very useful account of archaeological finds in Iron Age Atlantic Scotland, and their probable psychological meaning, which is worth quoting:

For the communities of the Atlantic Scottish Iron Age the dead were ever-present. They were buried below the floors and in the walls of houses, displayed and stored around the settlement, and they played a role in ceremonial occasions of various kinds. Some may have been close kin, or long-dead ancestors while others may have been despised and feared enemies. Certain body parts, especially the head, were seen as potent or active. They were regarded as retaining some power or essence associated with the dead individual or the community to which that individual belonged, and that power could be appropriated and manipulated in various ways. In many head-hunting societies, the taking of a head was seen as the capture of a spiritual force which would both enhance the well-being of one’s own community, and weaken the enemy. Whether trophies or relics, human remains in Atlantic Scotland could have long and complex ritual lives before their eventual deposition in contexts where they become visible archaeologically.

I have already written quite a bit on headhunting and the symbolism of the human head, so I wont revisit the topic too much further here.

What is key to understand here though is that headhunting—and/or the retention of heads or other body parts in general—is a cross-cultural and historical phenomenon that cannot be restricted to any particular time period, region, or society. I have often criticized hereditarian and Eurocentric accounts that take the current level of (particularly Western) European affluence, scientific knowledge, cultural norms, etc and then project them deep into the past.

The fact of the matter that is that the European peoples of a thousand years ago and before in many ways had much more in common with the different ‘traditional’ cultures all over the world than they do with the modern WEIRD people of today.

I actually think this is pretty obvious from just reading the classics of western literature even. I was immediately struck when reading the part of the Odyssey where Halitherses interprets Zeus’ sending of the eagles as an omen, to how similar it was to other beliefs and practices associated with prophecies and warfare from all over the world.

The Iliad describes a mourning ritual during the funeral of Patroclus, where his comrades shave their head and cover his body in their hair. This is very similar to other mourning rituals found across many small-scale societies, as I touched on here.

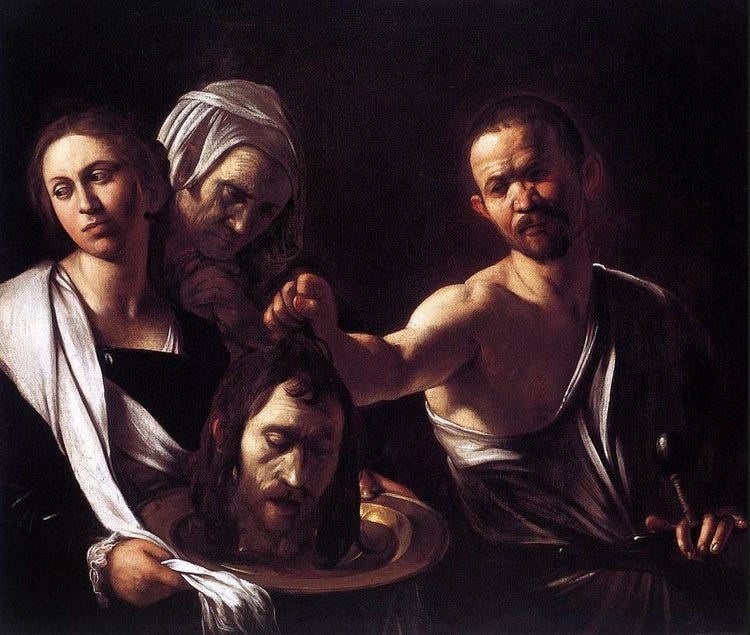

The psychological salience of the head and its removal and display come across quite clearly in the Bible, from the story of David and the Philistine, to the death of John the Baptist.

Before industrialization, infant and child mortality were consistently high across cultures, people did not have the same easy access to hygiene products and sanitation systems, and hunting and butchering animals were often necessary for subsistence. These socioecological contexts are very different from contemporary WEIRD ones, where people tend to be more ‘viscerally insulated’ from consistent exposure to blood, death and disease, which have contributed to a very different perspective and understanding of the world.

All of this brings me to the film The Northman (2022) by co-writer/director Robert Eggers.

Eggers says that he set out to make “the most historically accurate and grounded Viking film of all time.” On one level, this claim is somewhat absurd: the film is an adaptation of the story of Amleth, a legend for which is there is limited historical evidence. It isn’t even a particularly faithful adaptation either—Shakespeare’s version with Hamlet feigning insanity and the death of Polonius is closer to Saxo’s account. Many of the events in the film are also quite fantastic or physically impossible.

Yet there is a sense in which the film may well be “the most historically accurate and grounded Viking film of all time,” and that lies in all the effort it devotes to expounding the worldview of its characters. This film brings you into a particular mentality, one that has been historically described as ‘primitive’, but which I consider meaningful, often quite sophisticated, and understandable considering the circumstances.

The story of the film is exceedingly simple and unsurprising: the opening lines of the film quite literally tell you what is going to happen in a voice over, over a shot of the location where the final scene will be set. This doesn’t matter though because the excitement and the mystery come from how the characters get from A → B, and this can only be understood in relation to their beliefs within their culture.

The Northman contains many of the practices and themes that I’ve been reading and writing about over the last few years. Initiations, magic, omens, animal intelligence, animal mimicry and violence (see also my friend Cody Moser’s work on this), disguises, the removal and display of heads, ritual mutilation, wife capture. I could probably go on.

If you haven’t seen the movie I highly recommend it. It just came out in the United States, so I might wait and do a part two spoiler-heavy post here evaluating some of the mythological elements after more people have seen it.

If you have seen it, check out Robert Eggers’ interview with Slate explaining some of the historical elements. Historian Neil Price, who has written some fantastic books on the Vikings, was a historical consultant on the film and has an interview with Inverse that’s also worth checking out.

The great thing about The Northman to me is it presents a largely non-judgemental portrayal of a very different cultural context, without pushing any particular moral or ideological agenda regarding how that society ought to be interpreted. Of course, it is a work of (historical) fiction, but one that in my view is presented with the mentality of a good anthropologist.

Postscript [minor spoiler]: note that Eggers still WEIRDed down the tale in some ways: in Saxo’s account Amleth actually takes a second wife before the end. This would conflict with the love story elements Eggers presents in the film, so it’s understandable that he wouldn’t include it, but its absence also makes sense as most—not all—WEIRDos are opposed to polygyny.

Very excited for the more in-depth discussion of the ritual use & ASC's in the film!

Excellent post! It's interesting that among mainstream Mormons there is a backlash against polygamy, which makes them more ardently opposed than most WEIRD. See the Deseret News's reaction to the Short Creek Raid against fundamentalist polygamists: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Short_Creek_raid

The SLC Mormon owned newspaper was one of the only outlets that supported the feds breaking up polygamist families. Narcissism of small differences, and all that. Displaying disgust to demonstrate they really were done with the polygamy business.

Larger point still stands, of course, as there are hundreds of thousands of fundamentalists who still support polygamy.