The Innu people of Canada have a tradition of slaying a “great beast” as it emerges from its “winter bed”.

This animal is referred to by many names—“short tail”, “great food”, “black beast”, and most importantly, “grandfather”.

When the den housing the hibernating beast has been uncovered, the Innu hunter approaches the lair and makes a kind of formal announcement: “Come out grandfather!” he says. This may be repeated up to three times if there is no response from within. If the animal is female, it is thought that she will not respond to “grandfather”, and the announcement is repeated with the word “grandmother”.

There are multiple variations of this formal address: “My grandfather, I will light your pipe!”, “Show me your head, grandfather.”, “Come out grandfather, already it [the sun] is warm enough for you to come forth.”

As the beast emerges from its lair, the proper method of dispatch is with a blow from an axe, though in more recent times a hunter may have a rifle with him in case of failure or emergency.

After the animal has been killed, some procedures are necessary to show proper respect to “grandfather”. A bit of tobacco may be left in its den as tribute, in the hopes that another beast will occupy the same lair next year.

Similarly, a special pipe of birch bark may be crafted, with tobacco put in, which is then placed in the mouth of the carcass, “for a friendly smoke with his conquerors”.

Anthropologist Frank Speck notes the seriousness with which these ritual procedures are followed, even when they may come at significant costs to the hunters,

To give the newly slain bear a small amount of tobacco in his mouth is a practice observed in one form or another everywhere among these tribes. The more conservative Indians will not skin or cut up the bear until this is done. A story along this line is told by the hunters at Lake St. John of a father and two sons a number of years ago who had killed a big bear in March, when the weather had turned warm for a short spell, about a day's journey by snowshoe south of the former trading post of the Hudson's Bay Company at Metabechouan. They, being on their way out of the bush for the first time that spring, had exhausted their winter supply of tobacco some time before and, consequently, had none to offer to the “great food.” The father, however, decided to camp at the place and send one of his sons in haste to the post for the needed drug. It took the boy two days and a half to get to the post and back, and by that time the carcass was too much blown by the flies to use, and the meat was lost. A sacrifice to orthodoxy!

After a hunt, when referring to the slaying, the hunter is likely to say something like “I have killed black food,” rather than referring to directly to the animal, so the spirit of the great beast does not know what is being referred to or who killed him.

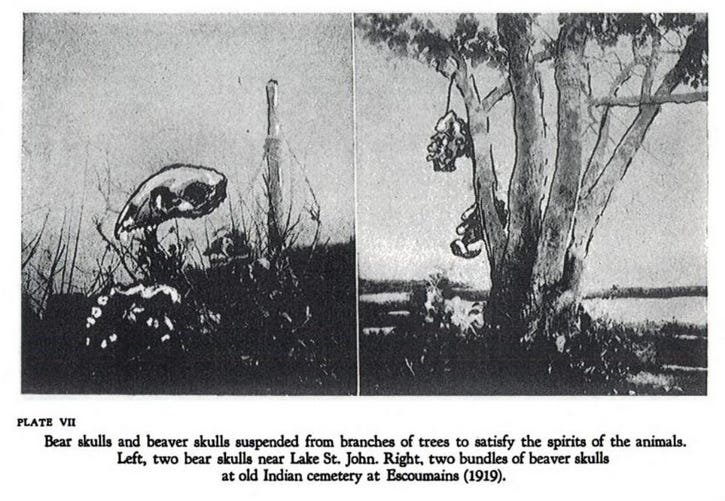

Speck discusses further the practice of placing the bear’s skull in a position of prominence to honor the deceased animal, writing that,

It is a belief among all these Indians that one of the sources of spiritual satisfaction to the slain bear is to have his skull set high upon some prominent point of land near a waterway frequented by the Indians, so that long after his demise he can enjoy the sight of the world afoot in winter, afloat in summer, as he did while he was living.

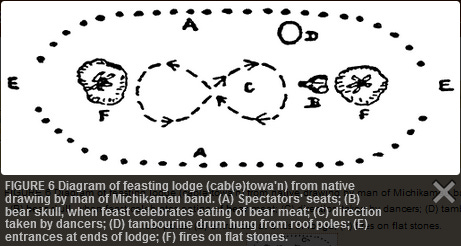

A great ceremony and feast are also conducted to conclude the proceedings.

Notably, some similar beliefs and practices are found all across the northern hemisphere, with special emphasis on the importance of the bear hunt and its taboos, ritual feasting, and ultimately funerary veneration.

Among the Copper Inuit of Canada, anthropologist Diamond Jenness says that killing a bear “was the hunter's greatest glory,” and describes a bear hunt where a mother and her cub were killed by a named Ikpuck. Jenness notes the belief that even when dead, bears should be treated with caution and respect, “So the prudent Ikpuck placed a needle-case beside the mother, and a miniature bow and arrow beside the cub, that they might not travel empty-handed to the spirit-home of their kind.”

After a hunt, the Yukaghir of Siberia try to trick the spirit of the deceased bear, explaining that it was really an elk, or someone from another society (such as the Yakuts) that really did the killing, and not the hunter:

Grandfather, of the earth master, us well mind!

To thee not we in such a way have done,

A Yakut thus did;

Thy silver bones we shall put into a house.

The Ainu of Japan and Siberia would also have special bear feasts, and place bear skulls in positions of honor.

Anthropologist Emiko Ohnuki-Tierney describes the extended process of capturing and raising a bear cub before the special feast and ceremony among the Ainu,

Over and above all the deities in the Ainu pantheon, the bears, or iso kamuy (Ursus arctos collaris), occupy the throne of the supreme deities. Their power as deities is a generalized one, providing food and looking after the general welfare of the Ainu. More than any other single behavior of the Ainu, the importance placed on the bear deities is most succinctly shown in the cultural complex of bear ceremonialism. In contrast to a simple rite which the Ainu males perform for a bear killed in the mountains, the entire process of the bear ceremonialism takes at least two years and consists of capturing and raising a bear cub, the major ceremony, and the after-ceremony.

The entire event starts in the spring when men go to catch alive either a newborn cub in the den or a cub strolling with its mother shortly after coming out of hibernation. They capture a cub of either sex with equal enthusiasm. The cub is called kamuy mis (deity-grandchild) and is regarded as a deity and a grandchild at the same time. The family of the man who captures the cub becomes the host family. The cub is raised inside the house until its claws become too dangerous, when it is transferred to a “bear house” or a cage outside the host's family. If the cub is newborn and requires nursing, any woman in the settlement who is nursing her baby will nurse the cub at the same time. (Since the introduction of dairy farming in the recent past, cow milk was usually fed to the bear.)

Although the oldest woman of the host family is officially in charge of the care of the bear and plays an important role in the bear ceremony, the care of the bear is a welcome enterprise for the whole settlement, and all participate in feeding the bear with the best food even when food is not plentiful for humans. In summer they clean the cage every now and then and take the cub for a walk and bathe it along the shore. In winter they insert twigs and grasses between the logs of the cage to keep the bear warm. When the bear is pleased, it shows its satisfaction by drooping its ears, and the Ainu find it most rewarding to see this.

While it’s clear that many aspects of ‘bear ceremonialism’ represent a shared historical tradition which diffused across numerous societies throughout the northern hemisphere, even in other parts of the world bears seem to have exhibited a particular fascination.

Among the Veddas of Sri Lanka, the bear is said to be the only animal they really feared. The bear’s true name is rarely mentioned, and instead they are spoken of only as “enemy”. The Semang Kenta of Malaysia would not eat bears at all, because they believe they were once men.

For the best available overview on bear ceremonialism, see ‘Bear Ceremonialism in the Northern Hemisphere’ (1926) by A. Irving Hallowell.