Mate choice is one of—if not the—most popular topics of study in evolutionary psychology. Much of this research has focused on sex differences in mate preferences, and has been claimed to be supportive of “universal sex differences in preferences for attractiveness and resources”. Consistent with this, Walter et al. (2020) write, based on the results of their 45-country sample study, that “Men, more than women, prefer attractive, young mates, and women, more than men, prefer older mates with financial prospects.”

Overwhelmingly, however, these studies tend to be conducted in industrialized and usually Western nation-states, and often among college students in particular. For example, despite the virtues of being a relatively large cross-country sample, more than half of the study population in Walter et al. likely came from university samples. [Records were incomplete regarding sample type, but from the study sites that did keep records, more than half (~53%) were from university samples]. Recognizing the shared socioecological context of these samples is extremely important.

In industrialized or industrializing societies, sex differences in ‘preferences for resources’ (or rather, financial prospects), make a lot of sense to me. Many occupations in capitalist nations are quite incompatible with the demands of childcare.

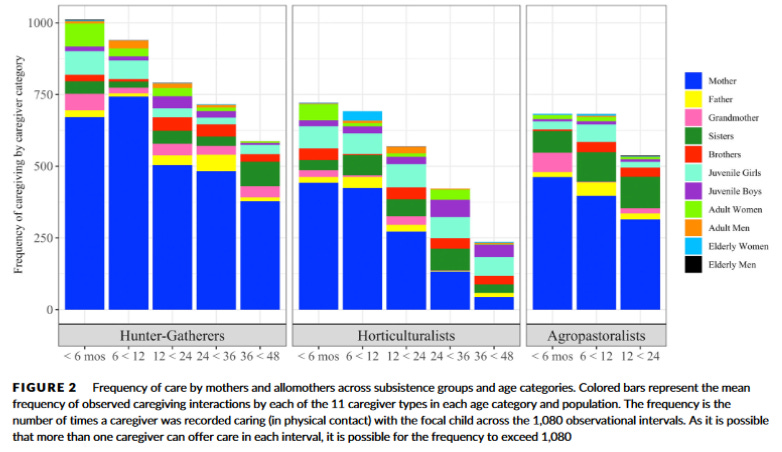

Across cultures, during the early years of a child’s life, mothers tend to do the majority of direct caregiving. If a woman has to juggle more direct caregiving responsibilities (particularly in the early months or years of pregnancy, nursing, and then weaning), along with work, potentially having to commute, etc, clearly this imposes greater demands on them than the father. Anthropologists have known for a long time that a key aspect of the sexual division of labor stems from the compatibility, or lack thereof, of certain kinds of work with childcare demands.

So, logically, I also would expect women in capitalist nations to commonly have a greater preference for men with good financial prospects than the inverse. But this does not necessitate an evolved psychological sex difference in preferences for partners with resources.

I am skeptical about any intrinsic, ‘evolved’ psychological sex difference in preferences for partners with resources or resource prospects: instead, I think preferences for resources for both sexes should be attuned to local socioecological context.

As I will show, in many contexts it appears that men exhibit an equal or greater preference for a partner with resources, or skills in generating them, as women do.

In a survey of remote Shuar hunter-horticulturalists of the Amazon, women and men exhibited no difference in preferences for resource related traits [edit: although study 2 did find a sex difference], while UCLA students followed the predicted trend of a stronger preference among women. Shuar women and men tended to rank physical attractiveness low on their list of preferences, and resource related traits very highly. Anthropologist Elizabeth Pillsworth writes, “As a male participant commented, and several others expressed, when doing the task, “If a woman cannot make manioc beer [the principal beverage] or care for the children or grow manioc [the staple food], what good is being attractive?””

One popular evo psych notion is that men’s main motive for polygyny is to “gain sexual access to more women.” This is certainly a commonly reported motive, but it does not appear to be the primary motive for a lot of the polygyny we find cross-culturally, where in fact wives are commonly sought out and valued for their labor contributions. Among the Tonga of Zambia, anthropologist Elizabeth Colson notes that one of the more important motives for polygyny, “is to be the head of a large homestead and to have the joint labour of a number of wives and their children to work the man's own field.”

Among the Tupinambá of Brazil, French missionary Claude d'Abbeville was told,

We know that a single wife is sufficient for a man and that it is not to satisfy our lust that we marry many women, but only with the intention of becoming greater and to have them work in the house and till the fields… And then the men are frequently killed in battle, and there are many single women in large number who cannot find a private husband [MC: one for themselves alone] we consider it necessary to permit the giving of several wives to one man. [emphasis added]

Anthropologist Rafael Karsten, discussing another Jivaro Amazonian population [related to the Shuar], writes that,

As to the reasons for keeping many wives, I once received the following answer from a Jibaro when I asked him about the matter: ‘I have a big house and I want many wives to keep it. One of my wives has to go out to the fields where she works nearly the whole day. In the meantime I want another to take care of the house, of the children, and of the domestic animals, and to serve manioc-beer to guests who arrive. Sometimes someone of my wives is ill or with child and then I want another to perform her work. It is otherwise with us than with white people.’ [emphasis added]

Among the Mescalero Apache, anthropologist Morris Opler says that, “normally only sororal polygyny was encouraged: if a married couple had many children and the woman was overburdened with work, her husband might ease the situation for her by taking one of her sisters or female cousins (terminological sisters) as his second wife.”

Anthropologist Bernard Deacon gives a very useful extended description of the motives for polygyny among the Malekula of Melanesia.

A large number of men have only one wife, while the number of unmarried men and widowers is considerable. Prominent men, as, for instance, the sons of former chiefs, may have two or three wives, but it is only among chiefs themselves that we find the extensive polygyny of from eight to twelve or twenty wives. The reasons given by the natives for the practice of polygyny are threefold: to have a woman to work in the garden and at other women's labours; because of sexual desire; and in order to have a woman to tend the pigs, which are man's most valuable possessions. Where a man marries only one woman, the two first causes are principally operative. It is said that a man who has a constant desire for a woman, a nömur nen nimomogh, seldom marries more than two wives. In these two he is absorbed; he desires them constantly and intensely, and goes about with them everywhere for fear of someone “stealing” them. In fact it seems that the “monogamous” type of desire, with its intense preoccupation with one woman, can and does extend to two, but seldom further. On the other hand there is the adventurous, warrior type, nömur vaal, who will generally have a number of wives. Psychologically he differs from the nömur nen nimomogh, for while his desire is equally frequent, it is not so intimately bound to, and wrapped up in, one object. He shares himself equally among his many wives, all of whom, with one exception, stand to him somewhat in the relation of privileged concubines. A man of this type will take additional wives partly because he is attracted, successively, by new and younger women, but principally because of his desire for a great pig farm, each wife looking after five or six pigs. This desire to possess a large number of pigs outweighs the trouble which an extra wife involves, arising out of the jealousies and antagonisms between the women. [emphasis added]

Note that while sexual desire is indeed mentioned, emphasis is placed on economic motives in particular, in men wanting women to work in the garden and tend to the pigs.

Polygynous marriage systems often occur where women’s marriages are arranged, and their choices are restricted. Across societies on the South Coast of New Guinea, anthropologist Bruce Knauft finds that “female status is higher where male prestige is not defined through activities that depend on the appropriation of female labor,” adding that,

Among Asmat as among Purari, polygyny was crucial to male leadership. Not only were multiple wives vital to facilitate extensive affinal alliances and feasting relations, but a man, upon marriage, became the exclusive owner of the sago stands inherited by his wife from her clan. Control of these sago stands and the female labor to work them was critical to the leader; it enabled him to stage ceremonial feasts and to attract cognatic or distantly related men and their families to himself, thus swelling the size of his settlement. [emphasis added]

Describing the marriage system of the Tiwi of Australia, anthropologist Charles Hart writes that, “Compulsory marriage for all females, carried out through the twin mechanisms of infant bestowal and widow remarriage, resulted in a very unusual type of household, in which old successful men had twenty wives each, while men under thirty had no wives at all and men under forty were married mostly to elderly crones.” And this polygynous system was heavily motivated by economic concerns,

The other economic factor was an equally firmly held Tiwi belief, namely, that the most efficient food-production units were the biggest units. This was the argument most frequently used against the monogamy preached by the Roman Catholic missionaries. “If I only have one wife”, a man would say, “how can I be sure of eating? My wife will go out in the morning in one direction and I in another, and if we both return empty-handed in the evening, which is highly likely, then I and my family will starve.” But with a large work-force some of the members at least were likely to find something, and then everybody could eat. Even in 1953-54, when the Tiwi had all become Catholic and monogamous, Pilling noted the tendency for men to surround themselves with large collections of women, even though only one of these women was a wife. The big work-force ideal still prevailed even though most of the food was by that time supplied by the Mission. The ways in which a Tiwi could build up a large work-force under his control varied. Under Aboriginal conditions, which still prevailed in 1928-29 for most Tiwi, the best and most common way was by amassing large numbers of wives. These wives should, ideally, produce large numbers of daughters, who could then be exchanged for more wives. However, the age gap between husbands and bestowed wives meant that this ideal could not begin to work out until a man was well into his forties ; but to make it come about when he was in his forties a man had to get started much earlier - in his late twenties and in his thirties. [emphasis added]

Evolutionary psychologists often focus on mating, but remember that marriage is the cooperative partnership in which most human reproduction occurs, and the particular marriage system a society has reflects their socioecological context and cultural history.

Evolved psychological preferences are surely still relevant here, but to know what they are and how they are relevant requires careful attention to the cross-cultural evidence and an awareness of how the current WEIRD sample bias may skew our understanding and lead to premature assumptions.

I strongly suspect that women’s greater preference for financial prospects reflects a particular socioecological context rather than an evolved psychological sex difference. Although, as I touched on above, evolved sex differences in parental investment are relevant here, but they do not in my view necessitate an ‘evolved’ (i.e., ‘innate’, universal) psychological sex difference in preference for resources.

Good job unpacking a complex topic. I suspect the neolithic farming revolution magnified this evolutionary trait. What I would like to know is whether the same is true of involuntary human labor resources. Killing a man in battle, then taking his wife to help farm your manioc, is a sound survival strategy in the Stone Age. If you are Mesopotamian, you might have the revolutionary idea to keep the man alive and put him to work, too. Maybe by the time you have built a civilization for your children, they will have enough resources to obsess over their looks and invent bank accounts. We are such dreamers, we humans.

I see several references in their argumentation to Catholic missionaries. This makes me wonder to what extent their argumentation has been crafted specifically to target those missionaries.